There is a lot of discussion these days about the relative naval power of the U.S. Navy (USN) and that of The People’s Republic of China (PRC), the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). I find it tends to be either too alarmist or too dismissive, and moreover generally incomplete. That’s partly the fault of the medium(s) involved, X (aka Twitter) is a difficult medium for deep discussions. Most news and blog sites work off of word limits and usually take on just a particular subtopic. Academic papers are not approachable by most and while they go deeper, they also tend to focus on subtopics. So, I’m taking a stab at a more comprehensive yet approachable discussion of the topic. I’m going to spread this out over three posts. The first, this one, provides geopolitical and historical context. The second is the direct comparison between the PLAN and USN. The third brings allied (or potentially allied) navies into the discussion.

There are three primary sources of tension between China and the U.S. (and most of the world) when it comes to the Naval domain. The one that gets the most press is Taiwan and the possibility that the PRC will attempt to conquer Taiwan by force. The second is the Strait of Malacca, which I’ll get to. The third is the one I want to start with, the 9-Dash Line.

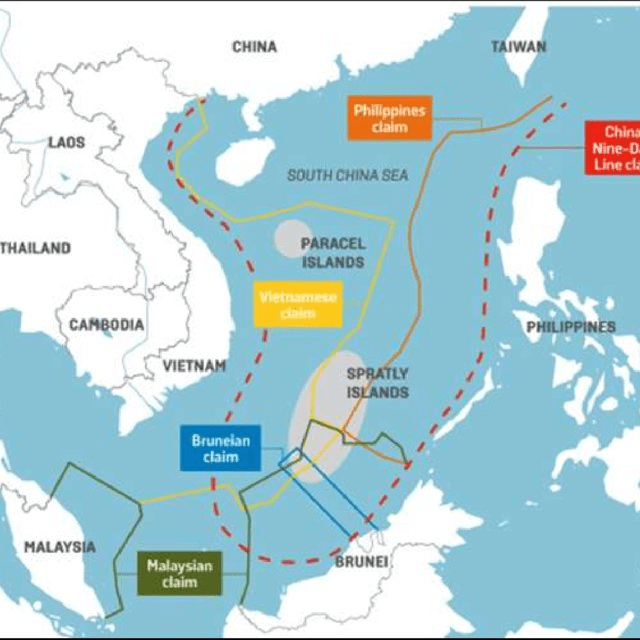

The 9-Dash Line is an outline of where China claims its territory extends, covering most of the South China Sea. This historically predates the PRC, having initially been established as the 11-Dash Line by the Republic of China. The problem with the claims should be obvious in the above image, the 9-Dash Line runs to just offshore the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam. It ignores the territorial rights of those countries in the South China Sea (SCS), or that much of the sea is considered international waters. BTW, for those who think “well it is the South CHINA Sea” I want to point out that this is not really true. The Vietnamese call it the East Sea. The Filipinos call it the West Philippine Sea. Indonesia? The North Natuna Sea. We use SCS as a convention, not as an indicator of recognizing China’s claims to it.

This next image shows what happens when you overlay the territorial claims of the various countries that border the SCS.

China claims a lot of territory that is claimed by other countries, countries that are for the most part friends or allies of the United States. The Philippines, which is a former U.S. Territory, has had a mutual defense treaty with the U.S. since 1951. Brunei and Malaysia, former British colonies are in a defense pact with the U.K., Australia, and Singapore called the Five Power Defense Arrangement (FPDA). Indonesia has close defense ties with former colonial power the Netherlands. Even Vietnam, which is a Frenemy of China’s, has a defense cooperation agreement with the United States. In other words, Taiwan gets most of the press but even if you ignore it the U.S. and some of its closest allies are on a collision course with China in the South China Sea over its territorial claims.

Next up, the Strait of Malacca.

Around 80% of China’s oil flows through the Strait of Malacca, which flows primarily between Malaysia and Indonesia, with Singapore along its southern end and Thailand its northern entrance. Moreover, the straight dumps ships into the Andaman Sea, much of which is under the control of India. India’s naval forces on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands can control traffic between the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. India may not have ocean territory disputes with China, but it does have a land dispute that frequently results in violent confrontations. From a strategic perspective it is imperative that China keep the Strait open to it even as it might go to war with countries that can block access. In a war you can imagine that China might find itself needing to seize control of the strait.

About 80% of Japan’s oil, and 40% if its overall maritime trade, flows through the Strait of Malacca, making it imperative that China not gain the ability to deny access to shipping to/from Japan. It’s not just Japan of course, 60% of Australia’s maritime trade passes through the Strait of Malacca. It’s almost 5000km from Australia’s northern coast to the Strait, which is one reason Australia must think about naval operations far beyond its immediate seas.

What you can see is that the Strait of Malacca is one of the most important maritime routes in the world and at the very center of potential conflicts China could be involved in. Even a land war in the Himalayas could result in a massive, naval-oriented, war for control of the Strait.

Last on this list is Taiwan, which I’m going to spend less time on despite it being the most likely flashpoint. It’s a set of islands, the biggest being Taiwan Island aka Formosa, that are part of the Republic of China (ROC). The ROC used to rule the mainland but were pushed out by the Communists, who were unable to dislodge the ROC from Taiwan. The PRC maintains a strong urge to take control of Taiwan and is preparing militarily to be able to do so. The U.S. maintains an official policy that Taiwan should be re-integrated into mainland China as long as it is done peacefully. Unofficially, particularly since Xi Jinping came to power in the PRC, we’d prefer it remain independent. We maintain a policy of “strategic ambiguity” on if we’d commit military forces to defend Taiwan should China attempt to seize control with military force. On the other hand, it is pretty clear we are preparing to come to Taiwan’s aid. Again, this is largely the result of the direction that Xi has taken China. Before his ascension to power the U.S. was trying very hard to balance improving relations with China against the desire to see Taiwan retain self-determination.

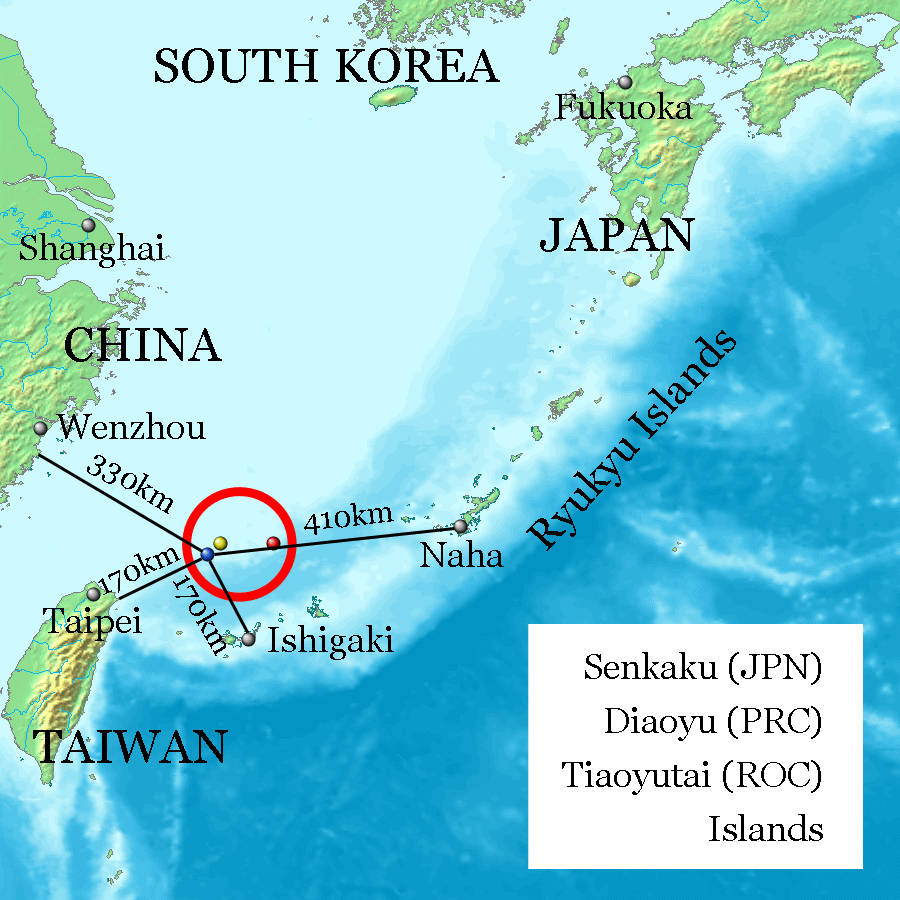

Control of Taiwan has implications well beyond Taiwan itself. That 40% of Japan’s maritime trade going through the Strait of Malacca first has to travel through the South China Sea. Chinese control of Taiwan would threaten that trade, in part by allowing China to control more territory within the 9-Dash line and in part by giving them a major base for threatening Japanese territory. For example, China and Japan have a dispute over ownership of the Senkaku Islands off of Taiwan. Japan also has a strong supply chain relationship with Taiwan, particularly over semiconductors, that would be threatened in a PRC takeover.

The friction between Japan and China has many other dimensions that I’m not going to explore here but are important to the balance of forces in the region. Japan is the most likely ally to join the U.S. in helping defend Taiwan if we were to decide to do so. It is also the country in the immediate region that we are most likely to put our full energy, including if necessary nuclear forces, into defending. It is the country on, and within, the First Island Chain that we have the most military forces on including the only aircraft carrier homeported outside the United States. And with that in mind it is time to talk about the lines of Island Chains, because that is where the main discussion of naval capabilities is focused.

While you hear a lot about the “First Island Chain”, and occasionally about the “Second Island Chain”, the U.S. Island Chain Strategy identifies 4 such lines of islands. You can see them in the image above. Two of the interesting observations here is that historically the U.S. was able to use bases in the First Island Chain to support operations on the Asian Mainland. U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay and Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines were the two largest overseas military installations before the U.S. left in the early 1990s. They supported the wars in Korea and Vietnam.

Today the only major U.S. Navy bases in the First Island Chain are in Japan. If you look at the map above, you can see how relatively difficult it would be to support an operation in the South China Sea or Strait of Malacca from Yokosuka in Tokyo Bay, where the US Navy Seventh Fleet is headquartered. The U.S. does have bases elsewhere, for example a recent return to Subic Bay, that it could use for resupply, but they don’t support the kind of mass that would be needed in a China fight. That is one problem. Another is that bases in the First Island Chain are close enough to be threatened by high volumes of surface-to-surface missiles from China.

Indeed, the overall problem is that bases in the First Island Chain used to represent where we would fight from while the Second Island Chain bases represented logistics nodes in supporting the First Island Chain bases. Increasingly we are having to plan to fight from the Second Island Chain bases, not just use them for logistics support. They also are under some threat from surface-to-surface missiles (and drones), and we have to deal with that as well. But it is another topic.

Finally, I should mention the Third and Fourth Island Chain. They give the United States considerable depth for both logistics and long-range strike. Military facilities at Wake Island have been, somewhat secretly, expanded in recent years. U.S. Special Forces have practiced defending a key radar installation on Shemya Island, in the north end of Third Island Chain. Of note about the Fourth Island Chain is that other than the Hawaiin Islands there are no islands before you get to the west coast of the Lower 48. When someone questions how defensible the U.S. mainland is from most forms of attack this is one of the reasons why. There aren’t potential bases for either logistics or long-range strike in the Eastern Pacific.

Now I think we can start to talk about naval strength and what it means in the context of the PLAN vs USN, and then on to what it means strategically. If we go back to the end of the Cold War the U.S. had 576 combat ships, 14 aircraft carriers, all surface combatants were Frigate or larger size, etc. China had 325 ships, but 200 of those were Missile Boats. Of the remaining 125 many were obsolete including WW2 leftovers and Soviet throwaways. It was a fleet designed to defend China’s coast but had little in the way of power projection. There would have been no contest in a fight for control of the South China Sea, the First Island Chain, or indeed most of the area within the 9-Dash Line; the U.S. Navy would have dominated with only a fraction of its fleet assigned to the task.

In the late 1990s through early 2000s the above chart shows the PLAN purging its obsolete missile boats, submarines, and other ships as it started to build a force more oriented towards major combatants and blue water operations. By 2015 they had a substantially modernized fleet including a greater focus on large ships. Along the way they surpassed the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) aka Navy in tonnage in 2013. That’s another interesting fact to keep in mind, that up until just over a decade ago the JMSDF was the more powerful Navy as measured by the more important (than number of ships) tonnage measure. In that same time period, the USN fleet shrunk from its high of 576 combat ships to 289 combat ships, and we’ve been pretty much stuck around that number (+/- 10) ever since. Meanwhile the PLAN fleet continues to grow, with an emphasis on larger ships. In 2015 they had 21 Destroyers, by 2020 it was 33. In 2024? 501. They’ve also gone from 0 to 2 (+1 in sea trials) aircraft carriers. Those are the numbers that drive alarmist view of the power balance between the PLAN and USN. On the other hand, the PLAN has not been adding nuclear attack submarines (SSNs)2 nor increasing the (already large) number of Diesel Electric attack submarines (SSKs). This gives a huge clue to their strategic intent, at least for the next few years. Beyond that I will leave discussion of fleet composition and capabilities for the next part of this series.

The reason I introduced fleet composition here is that claims of growing Chinese naval superiority vs. the U.S. depends on geopolitical focus. In 1990, 2000, or even 2010 the USN would have easily defeated any naval force put out by China within the First Island Chain. “Wiped the floor with them” would be a good expression. By 2020 that was no longer such a clear answer. As we enter 2025 it is looking that by perhaps 2027 the USN would lose a fight within the First Island Chain. Not only that, but U.S. forces also up to the Second Island Chain would be under serious threat.

The threat to the USN within the First Island Chain is not just from the PLAN of course. The rise in ballistic missiles putting U.S. bases at risk combined with any U.S. Naval force in and around the First Island Chain being subject to heavy AShCM, ASBM, and drone attacks makes operation in the South China Sea potentially untenable. Long-range air defenses on the Chinese mainland as well as its island outposts make operation of U.S. aircraft difficult. In other words, the whole A2/AD thing is at play protecting China’s naval forces.

Don’t equate my pessimistic description as a hopeless one however, the U.S. is obviously working on ways to counter the newfound strengths of the PLAN. But whenever I see budget discussions without sufficient budget for the USN (and other services), program cancellations and cutbacks, etc. that are needed in the IndoPacific theater I think about how quickly China is moving to make its ability to impose the 9-Dash Line on its SCS neighbors a fait accompli.

These discussions also often devolve into the topic of is the PLAN a Blue Water Navy or not, and then we get everyone’s opinion of what constitutes a Blue Water Navy. I think that’s a Red Herring. They have increasing Blue Water ambitions and operational capabilities, but their primary focus is closer to home. They want to re-take Taiwan and have sufficient naval strength to prevent the U.S. and its allies from stopping them. They want to make the 9-Dash Line their true territorial border and have sufficient naval strength to prevent the U.S. and its allies from stopping them. They want to have sufficient naval strength to keep open, and if need be, seize control of, the Strait of Malacca despite efforts by the U.S. and its allies to retain control of the strait. They want to have sufficient naval strength to then protect their supply of oil reaching the strait from the Persian Gulf region.

I didn’t read the blog this image is from, but I believe it covers the primary ambitions of the PLAN for at least the next couple of decades.

Although the PLAN is seeking to operate outside this region, for example establishing bases in the Caribbean to monitor (a.k.a., spy on) U.S. activity and potentially tie up USN resources, that is a sideshow. The PLAN isn’t going to sail a multi-carrier strike group task force into the Atlantic to go up against NATO for decades to come. They aren’t going to sail a task force to strike the Pacific Coast of the Lower 48, for decades to come. They aren’t going to sail a task force to help Russia in the Baltic Sea, for decades to come. A small set of ships for exercises, multinational task force participation, and showing the flag? Sure. But lots of countries with pretty modest navies do that. Is China building a Navy that can operate effectively anywhere from the east coast of Africa to the Third Island Chain? Yes, but they aren’t there yet. Not even close.

I mentioned the lack of growth in SSNs previously. It will be difficult for the PLAN to perform significant operations outside the First Island Chain without substantial growth to their SSN fleet. They will have a problem escorting their Carrier Strike Groups at long distances for example. Likewise, their ability to disrupt U.S. Naval operations much beyond the First Island Chain would be dependent on growing the SSN fleet. So, to a large extent, you can measure the PLANs reach by what they do about SSNs. They’ll telegraph their intent to perform major naval operations far from home when they start growing the SSN fleet significantly.

But when it comes to the First Island Chain, the U.S. already has a real formidable challenger on its hands.

Next up I’ll get into the real fleet comparison.